Analysis | Can Trump pardon anyone? Himself? Can he fire Mueller? Your questions, answered.

Analysis | Can Trump pardon anyone? Himself? Can he fire Mueller? Your questions, answered., On Thursday night, The Washington Post reported that the White House is actively exploring how to undercut the special counsel’s investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election and any ways in which that meddling may have been conducted in concert with people working for Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. Among the things apparently being investigated by the administration are the boundaries of the president’s pardon power, including whether it extends to him.

Analysis | Can Trump pardon anyone? Himself? Can he fire Mueller? Your questions, answered., On Thursday night, The Washington Post reported that the White House is actively exploring how to undercut the special counsel’s investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election and any ways in which that meddling may have been conducted in concert with people working for Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. Among the things apparently being investigated by the administration are the boundaries of the president’s pardon power, including whether it extends to him.

Additionally, a Republican who’s talked to administration officials told The Post that the White House hopes to begin “laying the groundwork to fire” Robert Mueller, the former FBI director tasked with the investigation.

The president’s ability to do those things are questions which we’ve explored ourselves over the past few months, given the large type-size of the writing on the wall.

So, allow us to recap.

Can Trump pardon his family and staff?

Yes — for certain crimes. When we looked at this in April, wondering whether Trump could pardon his former national security adviser Michael Flynn, we spoke with P.S. Ruckman, a professor at Rock Valley College in Illinois who runs a blog called Pardon Power.

“The conventional wisdom or the Supreme Court jargon to-date suggests that a president can pardon someone before, during or after conviction,” Ruckman said. “Is it possible Trump could pardon for crimes he may have committed in some period of time? Absolutely, yes.” …

The power of presidential pardon is exceptionally broad. Could Trump pardon everyone in America for crimes they may have committed over a period of time? Yes, Ruckman says — with the caveat that the crimes would have to be federal crimes or crimes committed in the District of Columbia. (He explained that, in the early days of the presidency, pardons for local D.C. crimes actually happened, including, according to his data, a pardon for chicken theft in the District.)

The go-to example of a president pushing the boundaries of the power to pardon is Gerald Ford, who offered a blanket pardon to Richard Nixon after Nixon left office in disgrace. That’s Ruckman’s point in the first paragraph: The Constitution defines the power to pardon so broadly that it allows pardons for things for which no charges have been filed or even identified. So Trump could, today, pardon Flynn for nearly anything he wanted to over any period.

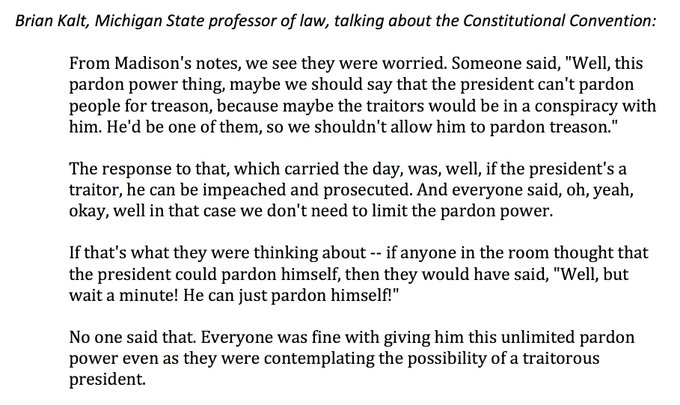

In fact, as Brian Kalt, professor of law at Michigan State University and author of the book “Constitutional Cliffhangers” told us when we were looking into the president’s ability to self-pardon, the president can pardon someone for something they didn’t do. Before the 2016 election, Kalt made the case that Barack Obama could pardon Hillary Clinton for any possible federal crimes related to her email server, simply to protect her from the possibility of Trumped-up charges being levied against her.

However! There are some boundaries. As Ruckman noted, it applies only to federal crimes and crimes within Washington, D.C. If Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner were charged with sticking up a bodega in Queens, Trump couldn’t do much about it.

There’s another pertinent caveat worth mentioning, raised by Harvard University’s Laurence Tribe.

If Trump were to pardon Flynn, for example, Flynn might not then be able to assert his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination if questioned. After all, there’s no legal risk to Flynn regardless of what he says. (There are a lot of asterisks that apply here, of course, including that it depends on how broad the pardon was.)

That, if nothing else, may give Trump pause.

Can Trump pardon himself?

This one’s trickier. In short: Probably not.

From our May article on the question:

“We can all only speculate what would happen if the president tried to do it,” said [Kalt]. “We’re all just predicting what the court would do if it happened, but no one can be sure.” …

Kalt’s got an opinion about what the Supreme Court would do if Trump (or any president) tried to give himself a pardon: They’d throw it out. …

[A] pardon is “inherently something that you get from someone else,” he argued. That’s not explicit in the constitutional language, but, then, other boundaries we understand for pardons aren’t either, such as our understanding that there need not be a criminal charge before a pardon. …

What’s more, “presidents are supposed to be limited,” Kalt said. “The president has all of this power, but he has a limited term. If he was able to pardon himself, that would project his power well past his term.”

Kalt makes a number of other arguments worth assessing. His point in short? A self-pardon would certainly have to be evaluated by the Supreme Court, and there’s not much reason to think that it would be upheld.

But Samuel Morison, who specializes in pardon law, wasn’t so sure. He sees the vagueness in the Constitution’s wording as leaving a lot of space.

“My opinion is that in theory that he could,” Morison said. “But then he would be potentially subject to impeachment for doing that.” Morison’s rationale is simple: “There are no constraints defined in the Constitution itself that says he can’t do that.”

Impeachment itself is specifically carved out of the presidential pardon power within the Constitution, so if Trump were impeached, he’d have no counter to that action.

Kalt, though, pointed to the Founding Fathers to offer ways in which they expected the power to be constrained.

In our interview, Kalt mentioned that Nixon asked his attorneys before he resigned if he might pardon himself and received tentative approval. A number of people, including Walter Shaub, the recently resigned head of the Office of Government Ethics, point to a 1974 memo from the White House Office of Legal Counsel offering the opposite view.

“Under the fundamental rule that no one may be a judge in his own case, the President cannot pardon himself,” it read. However: “If under the Twenty-Fifth Amendment the President declared that he was temporarily unable to perform the duties of the office, the Vice President would become Acting President and as such could pardon the President. Thereafter the President could either resign or resume the duties of his office.”

In other words, Trump could temporarily hand over the reins to Vice President Pence, who could then issue Trump a pardon before Trump takes his power back.

Of course, that’s one opinion from the Office of Legal Counsel.

Again: It would be up to the nine people on the Supreme Court to evaluate.

Can Trump fire the special counsel?

Sort of. First, a quick reminder of how we got here.

Trump fired James B. Comey, the head of the FBI. His attorney general, Jeff Sessions, had recused himself from the Russia investigation, meaning that the two people in charge of the FBI’s efforts in that regard were deputy attorney general Rod J. Rosenstein and acting FBI director Andrew McCabe. Rosenstein, on his own initiative, appointed Mueller as special counsel to oversee the investigation in May.

In that role Mueller technically reports to the Justice Department, just with far more leeway than a normal investigator.

So can Trump fire him? In our analysis of that question last month, based on a thorough look at the question from Jack Goldsmith, we created a flowchart to show how it might go.

|

| Analysis | Can Trump pardon anyone? Himself? Can he fire Mueller? Your questions, answered. |

All of those steps are explained in our story, but for our purposes here, we’ll focus on the yellow boxes. All of the non-yellow boxes come down to one question: If Trump asks someone in the chain of command to fire Mueller and they agree, Mueller is fired (with an exception as below). But box (1) preempts all of that.

The first question is whether Trump even bothers trying to follow the existing process to oust Mueller. Goldsmith’s analysis points to an argument that Trump could simply say that the mandates of those regulations violate his constitutional powers and fire Mueller directly. (An assessment from Marty Lederman at the Just Security blog rejects this idea outright.) Such a move would be challenged, understandably, but if it were somehow upheld by the courts, Mueller would be out.

Then, box (2) wonders if Sessions would stay recused. He might try to find a loophole that allows him to oust Mueller at Trump’s bidding, just as he had a hand in the firing of Comey despite his recusal. But there would no doubt be a lot of political blowback.

As for box (4), which assumes that someone in the chain of command agrees to fire Mueller, they’re constrained in their ability to do so. We used the example of Rosenstein agreeing to fire Mueller, since he is currently at the top of the chain.

Either they’d have to throw out the regulations binding the firing of Mueller (see Goldsmith’s post for a lot of detail on this) or they’d have to establish cause for firing him.

If either of those things is done, Mueller is fired. But the former would be exceptional and, given the bounds of the possible causes for firing special counsel — “misconduct, dereliction of duty, incapacity, conflict of interest, or for other good cause, including violation of Departmental policies” — it’s unlikely that a viable case for firing Mueller could be made in good faith at this point. If a cause can’t be found by Rosenstein, it’s hard to see how he could continue in that position.

So much of all of this — the pardoning, the firing — comes down to two questions: How courts would interpret actions taken by the president and the extent to which he’d face political pressure for taking those actions. If the Supreme Court’s conservative majority backs Trump and his allies in the Republican caucus on Capitol Hill do as well, Trump has a nearly free hand to do what he wishes.

The system is set up for checks and balances. The question underlying all of this is, will the legislative and judicial branches use their checks on the executive branch.

The answer? We may soon see.